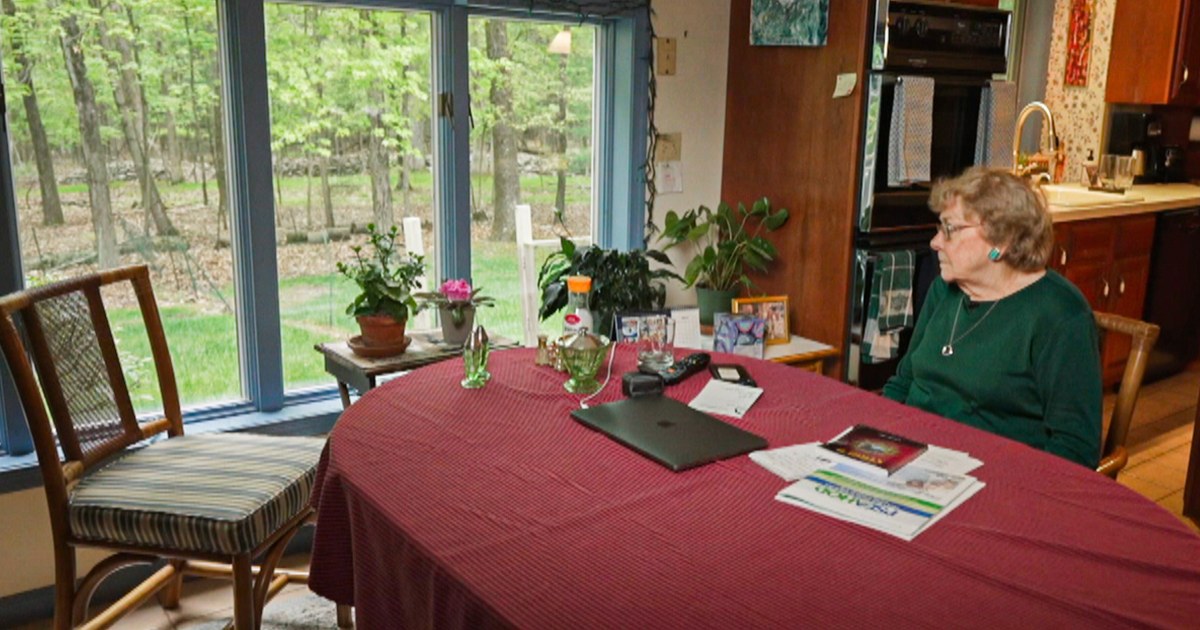

For 30 years, Jacqualyn James has taught American history and psychology to high school students in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, in the eastern Keystone State.

A graduate of Bucknell University, she became a teacher to support her family after divorcing her husband. “I felt it was very important for young people to learn the history of this country,” he told NBC News, having taught 7,000 students until his retirement in 1998.

During his teaching years, James paid him regularly pension, Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System. “I expected it to last my whole life,” the 88-year-old said.

While his $25,000-a-year pension will indeed continue, it is now worth half of what it was when he retired due to a setback in Pennsylvania law. That’s because of James and about 70,000 other retired communities workers they did not buy in the state cost of living adjustment Over 20 years of monthly payments. According to the Labor Bureau StatisticsEvery dollar of promised pension payments when James retires is worth 51 cents today.

James and his hapless former colleagues retired in 2001 before the state took effect. law Known as the Rising Act 9 pension benefits for government employees. Some of those 70,000 people over the age of 80 are in serious financial difficulties. Many do not have access to Social Security, as do about 40% of all public school teachers nationwide. National Association of State Pension Administrators.

Overall, the U.S. economy is humming, data shows, a situation that typically favors a sitting president in an election year. But fiscal concerns among voters in battleground states complicate the 2024 picture. Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin all have higher poverty indexes than states that vote reliably Democratic or Republican, an economic measure that combines four years of inflation with the current unemployment rate. , new analysis Bloomberg News shows.

Retired public workers like James aren’t the only ones facing tough retirements in Pennsylvania. About 2 million private-sector workers in the state, or 1 in 3 workers, do not have access to workplace pension plans, according to John Scott, director of the pension project at the Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonprofit that researches public policy. issues. Unless Pennsylvanians save more, state taxpayers will, Pew researchers predict is estimated $14.3 billion over the next decade to support older families with inadequate retirement savings.

“If you look at the data, the fewer people in retirement actually have access to a retirement plan,” Scott told NBC News. “Two million workers without access says a lot about why they feel insecure about their future.”

Even those who have saved money for retirement worry about their future. Victor Martens, 55, owns a small construction company in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania, with his son and contributes regularly to a personal retirement account. “You save enough for retirement, but then there’s inflation,” he said. “And the prices keep going up.”

An afterthought

For decades, James trust pensions, or pensions offered by corporations, were the most common means of retirement for workers. Today, self-directed savings plans such as 401(k) plans and individual retirement accounts, or IRAs, are the norm.

Amid this shift, many Americans have no retirement savings at all. Last fall, the Federal Reserve Board published a analysis More than 50% have a pension account in 2019, and more than half – 54.3% in 2022. The median amount in these retirement accounts is $86,900. For those nearing retirement age between the ages of 55 and 64, the median amount saved in a retirement account in 2022 was $185,000 nationally.

Having a retirement account does not necessarily mean that a saver will have enough money for a comfortable retirement. Approx two out of five According to the Center for Retirement Studies at Boston College, American workers have inadequate savings to maintain the standard of living they received while working. Although this figure has improved since 2019, it worries politicians.

In Pennsylvania, the share of households age 65 and older with annual incomes of less than $75,000 — an indicator of financial vulnerability — is expected to increase 17% from 2020 to 2035. research From the Pew Trusts.

The problem for many workers in Pennsylvania and elsewhere is that their employers don’t offer 401(k) plans, and without automatic paycheck deductions, saving for retirement is an afterthought. Small businesses in particular find it expensive and complicated to set up retirement plans for their employees, said Scott of the Pew Trusts. “You can save for retirement at work, but very few people do — only 13% of Americans,” he said. “There are a lot of steps you need to take.”

Fifteen states have found a solution to this problem—passing laws to mandate government-run automated savings plans that make it easier for workers to set aside money for retirement. Oregon became the first state to create an automated savings plan in 2017, and seven other states now have such accounts, with seven more to follow soon. Scott said the progress is encouraging — $1.3 billion has been earmarked for retirement for 850,000 workers in the six states with the longest-running plans.

A bill to create such a savings plan for Pennsylvania workers was proposed in 2023. programKnown as Keystone Saves, employees will voluntarily transfer their payroll deductions to a state-run fund managed by a third-party financial firm. The bill has yet to pass both legislative chambers.

Walt Rowen, third generation owner Susquehanna Glass Company Columbia, Pennsylvania is passionate about Keystone Saves. The factory, located about an hour west of Philadelphia, employs 40 people who make decorative bar and kitchen items.

“When I first heard about it, I thought this thing would be absolutely perfect,” Keystone Saves said. “They worked for us for 25-35 years. We know the impact – when they finally retire and they don’t have enough money put away, it’s going to be tough.”

Rowen said he considered creating a 401(k) plan for his employees about 15 years ago, but it would cost between $2,000 and $4,000 per employee to set up and operate. In addition, he said, many of his employees told him they would not attend.

Now, he says, offering such plans can help attract workers. “Over the years, people have said to me, ‘I’d love to work for you, but right now I have a 401(k) plan at work,'” Rowen said.Keystone Saves will solve that problem, he said.

$1.4 billion to Wall Street

The pending legislation would also address the 70,000 retired workers like James who have missed out on cost-of-living increases in their incomes for decades.

State Senator Katie MuthThe Democrat, who represents the 44th District near Philadelphia, is one of several cosponsoring lawmakers. bills of exchange the pensioner state says that the state owes them money to pay the pensioners. “It’s a collection of people who serve the public in various capacities,” Muth told NBC News. “This is a human rights issue”

Muth and other lawmakers supporting the COLA legislation to guess costs range from $89 million to $125 million. A lot of money to be sure, but Muth noted that Pennsylvania is Rainy Day FundThe state’s reserves for the financial crisis were $6.1 billion last fall.

What’s more, Muth said, the pensioners’ deprivation is especially stark compared to the fees that wealthy investment firms have collected over the years to advise pensions. “You can’t say the system is working when retirees don’t have this much increased cost of living, but their retirement dollars are being invested with $1.4 billion in investment fees to Wall Street managers,” he said.

James has written letters and emails to lawmakers about the problem, to no avail. Adding to his outrage: Pennsylvania lawmakers receive automatic cost-of-living adjustments in their pay.

One of those lawmakers is Republican Sen. Chris Douche, who chairs the government committee and refused to send the COLA bill to the Senate floor for a vote. Dush did not respond to a request for comment.

As efforts to help retirees decline, so do their numbers. Muth’s office said 3,444 beneficiaries died in the most recent year.

Michael Hurd is director and senior fellow of the RAND Center for the Study of Aging. Pennsylvania’s situation, he said in an interview, is an example of a state’s broken promise to provide pensions to workers that increase with the rate of inflation.

“The average age of these people is 83, so they’re obviously not going back into the workforce to supplement their income,” Hurd said in an interview. “Individuals are not in a good position to manage such risks. This is dishonest. This should not happen.”

Meanwhile, James’ daily expenses continue to mount. “Yesterday I got my monthly trash bill and it went up $18,” she said. “A lot of the things I used to love to do, I don’t think about doing anymore.”

He says he mostly watches the birds while sitting at the kitchen table feeding the birds.