“They know who to choose”

Stacy Zinn spent her first four years with the Drug Enforcement Administration in El Paso, Texas, where she investigated Mexican cartels. He went on to work in Afghanistan and Peru, chasing down narco-terrorists and cocaine traffickers. In 2014, the DEA transferred him to Montana and later put him in charge of offices in Billings, Great Falls and Missoula.

“When I got promoted and said, ‘You’re going to Montana,’ I was like, ‘Montana? Are there drugs in Montana?’” recalled Zinn, who retired from the DEA in October after 23 years.

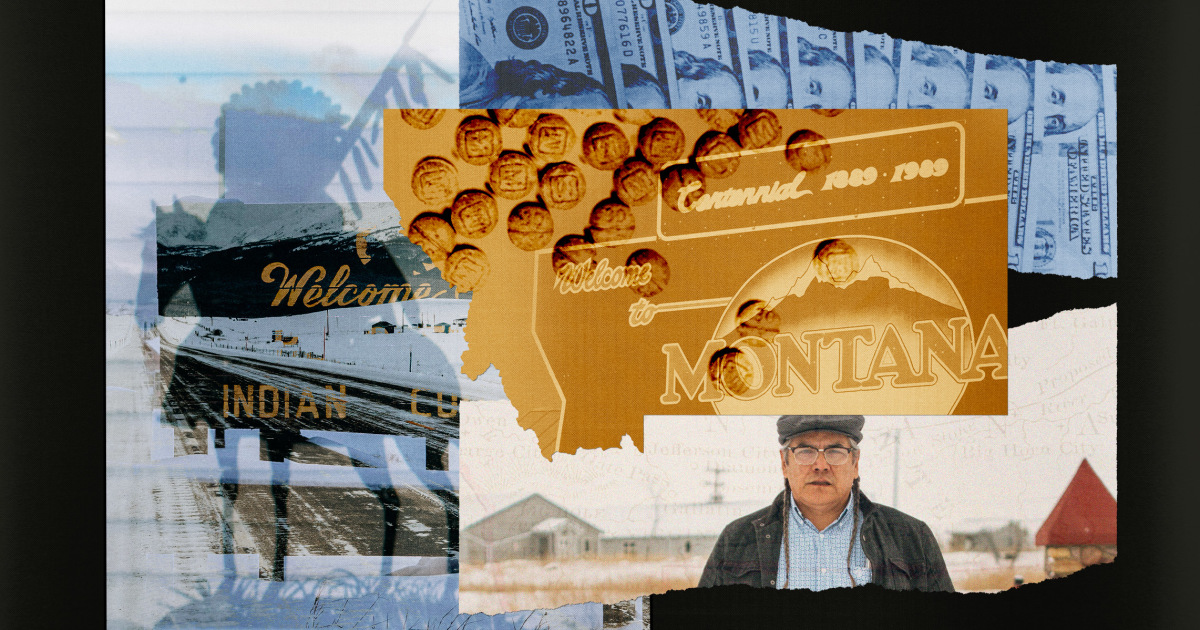

The state is sometimes referred to as the “last great place” in America. Its 1.2 million people are spread over 150,000 square miles of mountains, rivers, and mostly rugged terrain.

Domestically produced methamphetamine has long been Montana’s main drug scourge. But in the mid-2000s, the once-abundant meth houses in the Midwest and northern states began to disappear amid new restrictions banning access to the drug’s primary chemicals. Mexican cartels saw an opportunity and began to capitalize, law enforcement officials said, flooding the United States with a highly potent form of meth and specifically targeting local communities.

When Zinn arrived in Montana 10 years ago, he was shocked by the scope of the meth problem. But it was soon overtaken by fentanyl, which was cheaper to produce and deadlier.

A fake fentanyl pill, which can be made in Mexico for less than 25 cents, sells for $3 to $5 in cities with more drug markets, such as Seattle and Denver, and $100 in remote Montana. It was one of the few states that wasn’t the focus of Mexican cartels, but that soon changed, Zinn said.

“The income is only of this world,” he said.

Zinn was 1,300 miles from the southern border, where he was once again investigating Mexican cartels – the Sinaloa and Jalisco Next Generation cartel, or CJNG.

“I was excited,” Zinn said. “This is territory I know and understand.”

At first, he heard “whispers” about the existence of a cartel. But over the years, cartel partners have become bolder, he said, appearing more frequently as they seek to expand their operations.

“The cartel will send a team or individuals ahead of time to find out who is handing out small amounts on this reservation, who we can get our paws on,” Zinn said. “And then when they do, they own them. We have seen it many times.”

Women are often the main targets. According to law enforcement and tribal officials, cartel associates chased lone women onto the reservation and then used their homes as bases of operations.

“They know who they’re going to choose,” said Stephanie Iron Shooter, director of American Indian health at the Montana Department of Health and Human Services. “Just like any other predator-prey situation – it is what it is.”

The drug crisis has been most felt on Montana’s Indian reservations.

Between 2017 and 2020, the opioid overdose death rate in Montana almost tripled (from 2.7 deaths to 7.3 per 100,000 residents). In the decade to 2020, the overdose death rate among Native Americans was twice that of white Montanans. State Department of Health and Human Services.

In many ways, Indian reservations make ideal places for a drug operation to set up shop. Communities suffer from high rates of drug addiction and a lack of law enforcement.

The Northern Cheyenne tribe relies on two federally funded Bureau of Indian Affairs tribal police officers per shift to patrol more than 440,000 acres, home to about 6,000 residents, according to the tribal council. The neighboring Crow Reservation, the largest in the state, has four to six police officers per shift to patrol an area the size of Rhode Island, according to Quincy Dabney, mayor of the neighboring town of Lodge Grass.

“When we don’t have boots on the ground and people aren’t held accountable, it really becomes the Wild, Wild West,” said U.S. Attorney Laslovich. “I think you see more in Indian country than we do here in Montana.”

Complicating matters further are the reservations of sovereign nations, where local law enforcement agencies are restricted from operating without agreement with the tribe. Even when agreements exist, local and state authorities are often prohibited from arresting tribal members. And tribal police officers are strictly prohibited from arresting outsiders on the reservation.