When compliance lawyer Alexandra Wrage was invited to make an on-air anti-corruption argument on CNBC’s “Squawk Box” in 2012, she was surprised. “I remember laughing at the time and saying, ‘Well, is there anyone who is going to make a pro-corruption argument?’

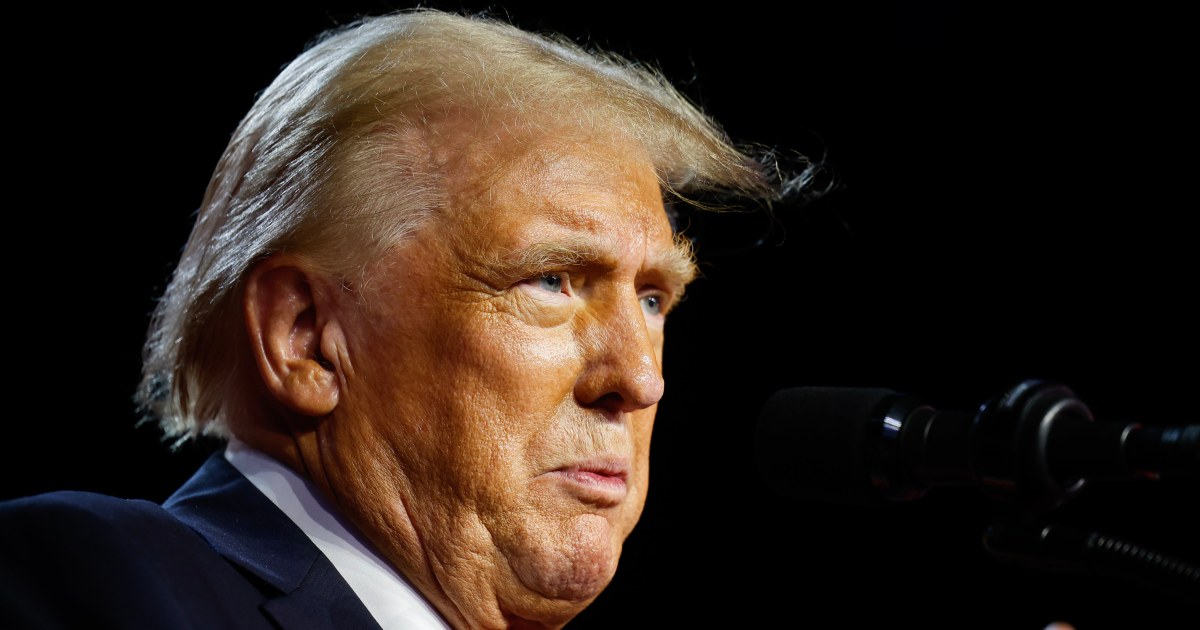

What they brought in was the president of the Trump Organization, four years before he first won the presidency. Donald Trump has called the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, also known as the FCPA, a “terrible law”.

Passed in 1977, the FCPA made it a crime for companies with US ties to pay or even offer to pay bribes to government officials in other countries. The law was the first of its kind in the world and was significant. Most countries have followed suit and passed similar laws, although experts say many are not as aggressive in fighting bribery as the US law.

“Every other country in the world is doing it. We are not allowed to do that. It puts us at a huge disadvantage,” Trump said in a 2012 CNBC appearance.

Trump then hung up and Wrage, founder of the anti-corruption organization TRACE International, answered the host.

“Well, the answer is certainly not to encourage an environment of lawlessness. “US companies never benefit from illegality.”

That memorable look as Trump entered the Oval Office in 2017 resonated In the halls of the Department of Justice, which handles the enforcement of the FCPA.

“We were all wondering – what’s going to happen?” said Fry Wernick, then supervisor of the Justice Department’s FCPA division. As a result, he said, several corruption cases in the last months of the Obama administration were quickly concluded before Trump took office.

A month into the first Trump administration, the president summoned newly confirmed Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and reported He shared his concerns about the FCPA, arguing that it is unfair that US companies cannot pay bribes to secure business abroad.

The news about this meeting spread quickly in Washington and Wernick the secretary of state fix the president. Tillerson, who previously served as CEO of ExxonMobil, “actually explained that no — the FCPA is a good law,” Wernick said, recalling hearing about that private meeting. “’This is legislation that helps level the playing field for US companies operating abroad. And you know, it can actually be a pretty useful tool.’”

The Trump administration’s anti-corruption record

Regardless of the discussion with Tillerson or other factors, the Trump years were “probably the strongest four years of FCPA enforcement ever,” according to Wernick. “More and more resources have gone into the FCPA division.” Fears that the first Trump administration was soft on corruption were overblown.

According to Wernick, the number of prosecutors in the DOJ’s anti-corruption division has nearly doubled during Trump’s first term, and the FBI’s International Corruption Unit has established offices at home and abroad.

But Drago Kos, former chair of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Anti-Corruption Task Force, said that while the first Trump administration met its international obligations to crack down on corruption, he feared “this time may be different.”

“I’m not too worried about the cases that the United States won’t investigate,” Kos said, because allies can bring charges against corrupt companies under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. “It’s worse when the US starts an investigation without any reasonable basis, because they will have other goals.”

Under the UN convention, each country’s government has discretion over how to enforce its anti-corruption laws, and Kos warned that this meant “the FCPA could be weaponized.”

In Russia, for example, bribery charges have followed President Vladimir Putin’s enemies. In 2003, Putin had Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the richest man in the country at the time. was arrested on fraud charges and sent to prison for ten years – seen as retaliation for his opposition to Putin. Several other opposition leaders have been jailed for corruption, and last week one of Putin’s top military officials, Major General Mirza Mirzayev, was arrested on bribery charges. the sixth military leader accused of corruption this year.

When Russian anti-corruption activist Sergei Magnitsky died in prison after being arrested for tax evasion, his business partner Bill Browder, chairman of Hermitage Capital, moved to pass a US law in his honor. In 2016, Congress passed the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, which allows the government to sanction, freeze assets, and bar entry to the United States against foreigners for human rights violations.

When Trump first took office, just months after the Global Magnitsky Act was passed, Browder worried that the new administration would not take advantage of this powerful new law. But he was pleasantly surprised.

“One of the good things about the previous Trump administration was that it was very hands-off,” Browder said. “He hired people who were quite decent and had an attitude of doing whatever they thought was right.”

Browder fears that without these advisers around him, Trump could go in a different direction in his second term. “I think they’re going to be very political about it. They will choose their targets,” he said.

“What [Trump] When Jamal Khashoggi was killed, it was to protect his friends like Mohammed bin Salman from Magnitsky sanctions,” said Browder, referring to the journalist’s murder, which led to calls for sanctions against the Saudi crown prince. “The fear is that it’s kind of inconsistently applied.”

Wernick, a former DOJ prosecutor, says he sees this executive branch discretion as an opportunity. “The world today is different than before. I think that enemy nations have an arrow at the moment,” he said, pointing to countries that exert influence around the world, such as China, Russia and Iran.

“All the countries I mentioned have huge corruption problems,” Wernick said. “Dictators and other leaders in these countries who don’t care that they are stealing from their people.” So Wernick suggested that the US could target enemies with corruption charges to complement sanctions.

“It was never intended that way,” Wernick said, but “there’s an opportunity to use the FCPA in a thoughtful way that can actually be a useful addition to foreign policy efforts. … It’s kind of an ‘America First’ approach that I think the Trump administration can quite embrace.”

Much will depend on who fills Trump’s key leadership roles.

This week, the president-elect announced that he will select Senator Marco Rubio for secretary of state. Rubio, who co-sponsored the Global Magnitsky Act, could be in a strong position to enforce the law against corrupt foreign officials.

For the Attorney General Trump chose Matt Gaetz. Trump announced his pick on the Truth social network, saying Gaetz would “root out the systemic corruption at DOJ and return the Department to its true mission of fighting crime.”

Trump’s transition team did not respond to questions about what crimes the new administration would pursue and whether corruption prosecutions would be a priority.

“Personnel is politics,” Wernick said. “Who he has around him is going to be important.”