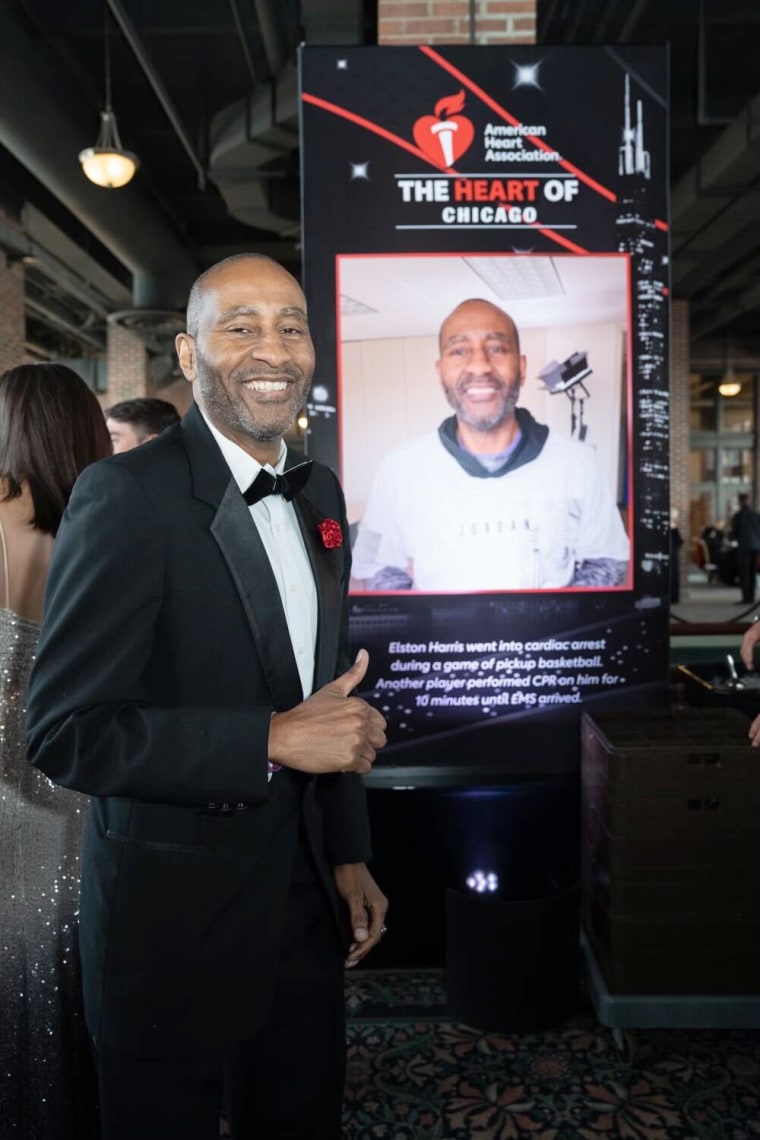

For Elston Harris, a heart attack seems like a generational curse.

Several men on the father’s side of the family, including Harris’ uncles, died of heart attacks. Harris, 59, a former college basketball player, suffered an almost identical fate after suffering a heart attack in 2017. indicates a heart attack he noticed that he had “minor” symptoms of back pain and trapped gas.

For Harris, the curse may have been a blessing in disguise: While being treated at Advocate Trinity Hospital, a medical center in southeast Chicago, he met cardiologist Dr. Sent to Marlon Everett. This includes putting God first, eating healthy, and focusing on His checks. But aside from Everett’s experience, Harris said he feels comfortable that Everett looks like him.

For more on this story, go here NBCNews.com and watch “Hallie Jackson Now” on News Now at 5 p.m. ET/4 p.m. CT.

“When you’re African-American or black, you’re more comfortable interacting with someone who says, ‘Well, he can grow here, or he can eat this, or I heard they do this,'” said Harris, who lives there. In Chicago. “So you’re more comfortable with people who walk similar steps.”

About 60% of black American adults have heart disease, and death rates from heart disease are highest among black Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups. American Heart Association.

Even so, Harris’ experience with a cardiologist like him is rare. A 2021 report The Association of American Medical Colleges found that only 4.2% of cardiologists are Black. An earlier study published in 2019 JAMA Journal of Cardiology Similar findings revealed that Black physicians make up only 3% of the cardiology workforce. In that report, 51% of cardiologists were white, and 19% were Asian.

Increasing the number of black cardiologists could mean better heart health for black patients.

“Underrepresented medical professionals are more likely to practice in communities where cultural sensitivity can build trust and where their presence has been shown to improve outcomes,” the AHA said in a statement to NBC News. “When it comes to heart health, this relationship is particularly important among Black Americans.”

Why are there so few black cardiologists?

Cardiologist Dr. located in Greensboro, North Carolina. Mary Branch said she first became interested in cardiology about 20 years ago after shadowing a white interventional cardiologist who was “very accepting of me.” The path to cardiology is arduous, and with four years of medical school, three years of internal medicine residency and three years of cardiology fellowship, in addition to several board exams, he said it can be a tough road.

Branch, a fourth-generation physician, said his path included financial strain and discrimination — among the barriers all too common for black medical students — and reasons why there are so few black doctors in cardiology.

Branch was the first Black woman to enter a cardiovascular fellowship at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. At one point during his retirement, he said, he lived in a hotel while trying to find safe housing.

Even without a place to stay, Branch said, he’s “still showing up” in retirement. “Indeed, God said you are needed,” he said. “So we have to move on. But it meant very difficult choices.”

Many Black medical students may also experience harsh microaggressions that may prevent them from becoming cardiologists, Branch said.

The margin of error may be “very small” for Black cadets, he said. While most medical students and residents of all races experienced high levels of mistreatment, blacks experienced more stress in medical school than whites, according to one study. 2006 study In Journal of the National Medical Association. Perceived stress stemmed from their minority status and experience of racial discrimination in training.

A study in 2021 Journal of General Internal Medicine It found that the proportion of black doctors in the US has increased by just 4 percentage points over the past 120 years. The study also found that the share of black male physicians has remained the same since 1940. Although little is known about the proportions of black women in cardiology, black women make up. doctors make up only 2.8% of the workforceaccording to A 2021 perspective in The Lancet.

Everett, who is a member of the Association of Black Cardiologists, a national organization that focuses on the harmful effects of heart disease on blacks, pointed to the lack of adequate training programs for doctors who want to become cardiologists. Most cardiology programs may only have three or four cardiology training positions, but “we just don’t get those training positions,” he said.

“Until there are programs that require diversity in training programs, we’re never going to have a lot of inclusion, especially in sought-after training programs like cardiology,” Everett said.

The organization also plays a role in recruiting Black patients into clinical trials with small numbers of Black participants. A 2021 to learn A study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association found that black adults are underrepresented in cardiovascular trials funded by the National Institutes of Health.

This may mean that doctors do not have the best knowledge about how to treat black patients.

“It’s very important to have more black patients in trials so we can get better data — and more data means better data and hopefully better outcomes,” Everett said.

‘A sense of comfort’

For many black patients, having a black cardiologist creates feelings of trust and comfort, which is sometimes difficult because of the medical system’s history of racism and mistreatment of black patients.

Nikita Ochner first saw Branch last year after doctors discovered a heart murmur they discovered during a sleep study. Oxner, 45, said she had never seen a cardiologist until now, and even being referred to one was “scary.” However, her fears subsided when she met Branch.

Under Branch’s care, Ochsner discovered that he had a condition that made it difficult for his heart to pump blood.

Oxner has a family history of heart problems. In 2019, hypertension caused the sudden death of his brother at the age of 31, and his grandmother died of heart disease at the age of 77. His father, who died of cancer at the age of 39, “hypertension, high blood pressure most of his life,” he said.

Oxner said that when he shared details about his brother and other family members with Branch, “he immediately understood.” Although he “didn’t feel good” about having surgery to implant a defibrillator in his heart, Ochsner trusted his doctor’s opinion.

“He was very compassionate,” said Ochsner, who lives in Greensboro, North Carolina. “He was very understanding, down to earth and relatable – and really helped me understand how this could change my life.”

As a black woman who often has to advocate for her health, Oxner said it “mattered to me” that Branch was also a black woman.

Branch said the added layer of trust and comfort often seen between a Black patient and a Black doctor can motivate patients to stay on their heart medications and stick to healthy lifestyle changes.

For example, “hypertension It’s a big thing in our community,” he said. A black cardiologist might as well be hypertension medicationhe said, “so they can connect and connect that way.”

Like Oxner, Kia Smith, 42, is another black woman seeking heart treatment from a black doctor. Smith, who lives in Ellenwood, Georgia, was referred to Atlanta Heart Associates cardiologist Dr. Camille said she saw Nelson. If she had chosen a non-black cardiologist, Smith said, she would have been treated as a “dramatic entrance” and treated. symptoms are relieved.

“At every turn, when I was concerned, he didn’t dismiss my concerns and my personal experiences,” Smith said of Nelson. “He also explained the science of it all to me and we were able to get to where I was confident I would be fine.” Nelson said Smith’s symptoms were caused by stress and recommended an exercise routine to get his heart into a healthier state.

Dr. Zeinab Mahmoud, a cardiologist and instructor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, said many black women feel heard and understood under her care. Having a provider who can understand the black patient’s experiences “builds that kind of trust and improves the patient-provider relationship,” he said.

“They are more likely to have their family members come or have their family and friends come to see me as well,” Mahmoud added. “I’ve seen this happen so many times I can’t even count.”

Attracting more black physicians to cardiology

Increasing the number of black cardiologists has been a focus of major health organizations in recent years.

AHA’s Scholars Program provides cardiology resources for Black students from historically Black colleges and universities, Where more than 70% Black medical professionals earn their degrees.

The organization is also focused on a broader effort: Strong education can help train the next generation of black doctors, nurses and researchers, the statement said. One of the main goals is to increase the number of Black students in graduate science, research and public health programs.

Like the AHA, the American College of Cardiology has implemented diversity efforts through it internal medicine program Introducing Black, Latino, and other underrepresented groups to cardiology.

“The problem is not only cardiology,” said Dr. Melvin Echols, ACC’s chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer. “All this is related to health. You see a significant, very low proportion of African American doctors. I think No. 1 what we’re trying to do is make it easier for people to actually get information and get resources.”

Harris, who survived a heart attack in 2017, said that “by the grace of God,” when her life was in danger, she turned to Advocate Trinity Hospital — a cardiologist she could trust.

“He was there during my episode, and we hit it off right away,” Harris said of Everett, the cardiologist. Harris has been under his care “ever since.”