This article is part of The Lost Rites, a series In America’s failed death notification system.

RAYMOND, Miss. – Gretchen Hankins arrived at a poor field in Hinds County Friday morning for her son’s body and answers. He didn’t get any.

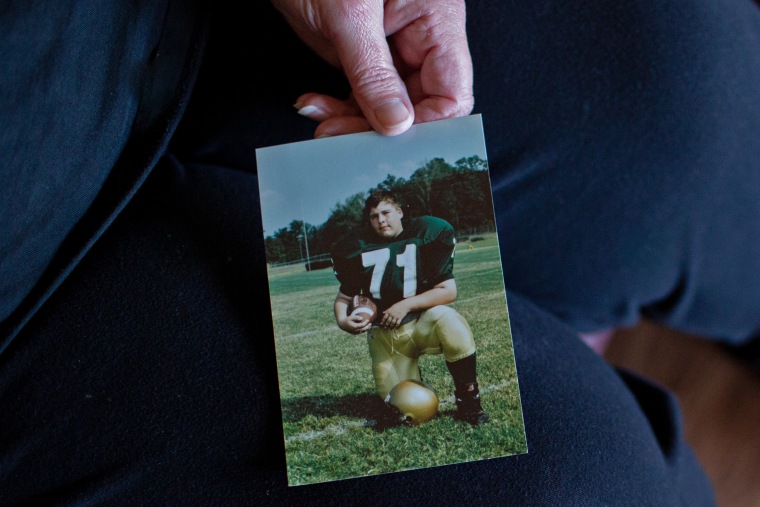

son of hankins, Jonathan David Hankins, 39, died of a drug overdose in May 2022, and his body remained unclaimed for more than a year as family, friends and police searched for him. Without anyone telling his mother about his death, he was buried in a grave marked only with a number: 645. He was one of them. several men who were buried without their families being told, sparked widespread public outrage after NBC News broke the story last year.

Early Friday, Gretchen Hankins stepped out into the poor field on the grounds of the county jail’s work farm for the first time to witness her son being exhumed so his body could be prepared for a proper burial. He said an employee of the Hinds County coroner’s office could attend the exhumation.

Hinds County Coroner Sharon Grisham-Stewart was also there, and Hankins began to question why no one had said her son was dead.

As Hankins’ sister recorded on the phone, Grisham-Stewart said the failure was not her fault.

“I don’t know about missing persons,” said Grisham-Stewart, who has held the elected office of Hinds County coroner since 1999. “I don’t know how to find people. I know how to determine the cause and manner of death. But I’m sorry if I’m having trouble searching for people. I don’t know how to find people.”

“But it’s your job,” Hankins replied, “and when you take it, you’re going to have to learn how to do it.”

Bailey Martin, spokeswoman for the state medical examiner, said county coroners must undergo a medical examination. 40 hour training course every four years, including locating and contacting next of kin.

While each county has its own procedures, Martin said, “the ultimate responsibility for death notification rests with the county coroner.”

Shortly after Hankins criticized Grisham-Stewart for not telling her about her son’s death, Grisham-Stewart told her she couldn’t be there. Hinds County Sheriff’s Deputy Hankins ordered his sister, friends, reporter and photographer away from the cemetery.

Grisham-Stewart did not immediately respond to a request for comment. A spokesman for the Hinds County Sheriff’s Department said members of the public should request access to the pauper’s cemetery because it is on jail property.

It was the first time Hankins had met Grisham-Stewart since learning of her son Jonathan David Hankins’ death in December when an NBC News reporter came to her door to break the news. investigation Failed death notices in Hinds County.

Documents obtained by NBC News showed that Grisham-Stewart’s office identified Jonathan Hankins’ body days after police found him dead in a Jackson motel room, but no one contacted his mother despite reporting him missing to authorities in neighboring Rankin. Count and Jonathan are listed in the federal missing persons database.

A Google search of Jonathan Hankins’ name by Grisham-Stewart’s office would provide information about his family and efforts to locate him.

After finally learning of her son’s death from NBC News in December, Hankins said she paid the county $300 to reclaim rights to his body and exhume his remains.

“I’m a mother, you didn’t contact me when my son was buried,” Hankins told Grisham-Stuart after arriving at the poor’s field Friday morning, according to a recording released to NBC News.

“Sometimes we don’t know how to reach out to families,” Grisham-Stewart responded.

Grisham-Stewart, who worked as an undertaker for nearly two decades before becoming Hinds County coroner, has not spoken publicly. failed notifications. Before the scandal, he This was reported by The Clarion-Ledger The newspaper reported in 2022 that the number of unclaimed bodies handled by his office has risen sharply over the past two decades — a trend repeated in large and mid-sized cities across the country in an era rife with opioid addiction, rising homelessness and increasingly fractured families.

In 2003, Hinds County sent 11 unclaimed bodies to paupers; In 2022, this number increased to about 40.

In light of the spike in homicides and deaths due to Covid, Grisham-Stewart told The Clarion-Ledger that she “went to bed every night praying that there wouldn’t be a murder or a car accident.”

The exposure of the dangerous death notices fueled and led to nationwide outrage calls for federal investigations. Jackson, Mississippi Police Department adopted his first policy on death notices in November. The coroner’s office has since left a copy of his policybut it is not clear when it came into force.

In the Hankins case, the coroner’s office has not said what it did to find or contact his family. The agency said it forwarded Jonathan Hankins’ information to the Jackson Police Department for notification purposes, but the police department said it never received that information.

At the gravesite, Grisham-Stewart told Gretchen Hankins that her office staff had received training from the Mississippi State Medical Examiner’s Office, but that training was not focused on finding people.

“But it wasn’t that hard,” Gretchen Hankins told Grisham-Stewart. “All you need is a computer.”

“Well, it’s hard when there’s death after death after death and you’re working 24 hours a day,” Grisham-Stewart said. “And you know the computer is on the desk. My work is outside.”

“It’s still inexcusable,” Hankins said. “If you’re going to do something, you’re going to have to do it.”

“I’m not making excuses,” Grisham-Stewart said.

Grisham-Stewart told Hankins that when her staff can’t find families, “we always hope the families can find us.”

But Hinds County — like most national coroners — does not write to a free searchable database maintained by the Department of Justice of the names of the unclaimed dead. NBC News in December published their names 215 people buried in Hinds County Pauper’s Cemetery since 2016 to allow families to locate their loved ones.

Grisham-Stewart told Hankins that she was “trying to make things happen now to try to do better” and that “it wasn’t intentional, it wasn’t intentional, it wasn’t forewarned.”

Hankins said he believes it was intentional. “Just because everybody’s here— I bet you 90% of them were your drug users or homeless and you don’t care.

“Well, I’m sorry you feel that way, but that’s not true,” Grisham-Stuart said.

“That’s true,” Hankins replied.

Hankins said she just wants to get her son’s body back and give him a proper burial.

Grisham-Stewart said it was “admirable”. But he told Hankins that he was not allowed to be in the poor field.

Hankins then went to find Jonathan’s grave, looking for his number, 645. A sheriff’s deputy stopped him before he could find him.

“Ma’am, you must go now,” said the deputy.

The deputy also said an NBC News reporter and photographer were not allowed to be there.

In a later interview, Hinds County Sheriff’s Department spokesman Othor Cain said members of the public must request permission to visit the pauper cemetery under an updated policy adopted last month by the Hinds County Board of Supervisors.

“This is not a public place,” Cain said. “It’s actually like walking into our detention center because it’s on the grounds of that facility.”

The poor man’s field – actually several different fields – is located off the dirt road leading from the working farm. There are no barriers blocking public access, but there are signs stating that unauthorized vehicles are prohibited.

Cain said he could not provide a copy of the updated policy because it would take “20 to 30 days” after the vote before it becomes an official document.

Hankins said his mortuary was able to exhume Jonathan’s remains on Friday — his service is scheduled for Feb. 10 — but he didn’t trust Hinds County and wanted proof that the remains were actually his son’s.

“It’s more like they’re hiding something, they didn’t even let me go there and see where he was buried. What are they hiding?”

After turning around, Hankins, along with his sister and some friends, got into their car and drove back down the dirt road and left the working farm.

“I wanted to see him,” Hankins said on the side of the road.

Then he started crying.