The barring favorite to win the Republican presidential nomination appears on the verge of victory in Iowa and leads by wide margins in national polls and other key states — except for one: New Hampshire, where a challenger has gained steam in recent polls, raising the possibility that the Granite State’s coronation could turn into a real contest.

If that sounds like a description of the current GOP process, it is. But it was also a set-up that could offer a useful lens through which to view the current race for the Republican primary season more than two decades ago.

There are obvious differences in tone and substance between George W. Bush and Donald Trump. But by the 2000 primary season, the trajectory of Bush’s candidacy was virtually identical to Trump’s this time around. The then-Texas governor spent 1999 building a stunning lead in the national polls, racking up endorsements and knocking out multiple challengers before the first votes were cast.

Trump’s 2023 continued the same way. In fact, Trump is the first Republican candidate since Bush to enter an election year averaging more than 50 percent support in the national poll. He’s also the first since Bush to have an average lead of more than 20 points this close in Iowa caucuses.

In Bush’s case, he had little trouble overcoming the Iowa caucus, winning 41 percent of the caucus vote — the highest share for a non-incumbent, and one that Trump surpassed in recent polls. Bush easily defeated his primary threat in the state, Steve Forbes, by 11 points. Unlike current Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, Forbes ran his campaign practically in the Hawkeye State, moving to the right by focusing on cultural issues. His caucus showing was respectable, but the campaign turnaround worried he was banking on it. Forbes trucked through New Hampshire, but he finished his studies there before dropping out.

But Forbes has never been a candidate to worry the Bush team in New Hampshire. It was John McCain, who had just made a remarkable effort in Iowa and made his case in the Granite State. The Arizona senator cast himself as a reform-minded political maverick, traveling the state on a campaign bus called the Straight Talk Express and happily fielding questions from all the reporters on board without a note. Long before Iowa, McCain was already in contention in New Hampshire, and even as Bush celebrated his caucus victory, it was clear that McCain was a threat to win New Hampshire.

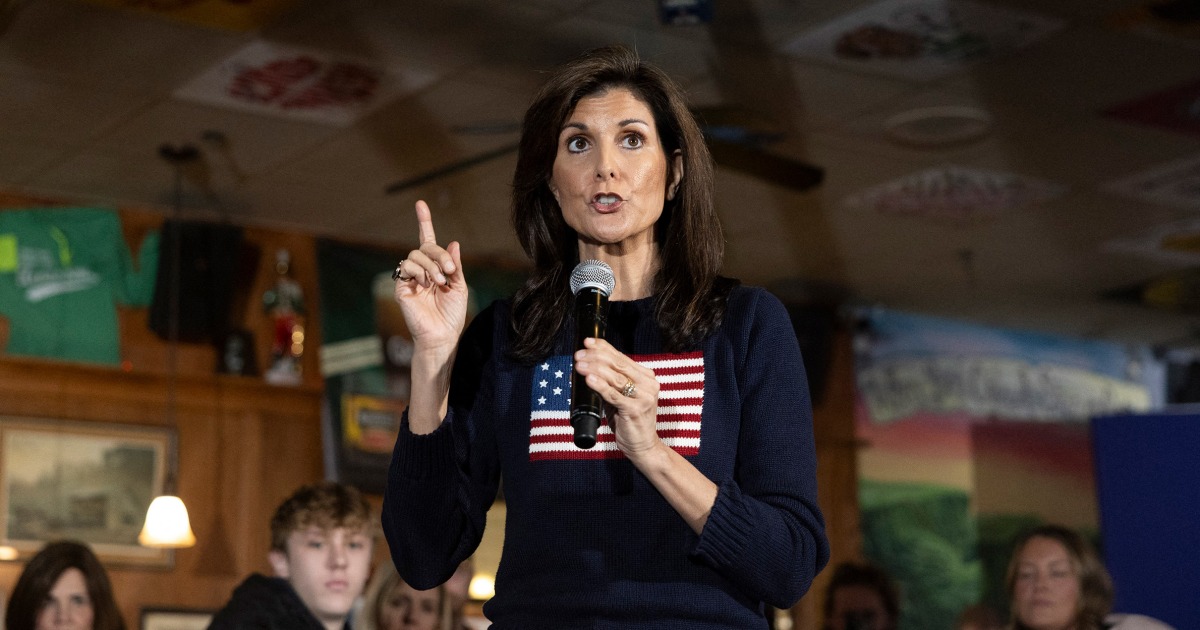

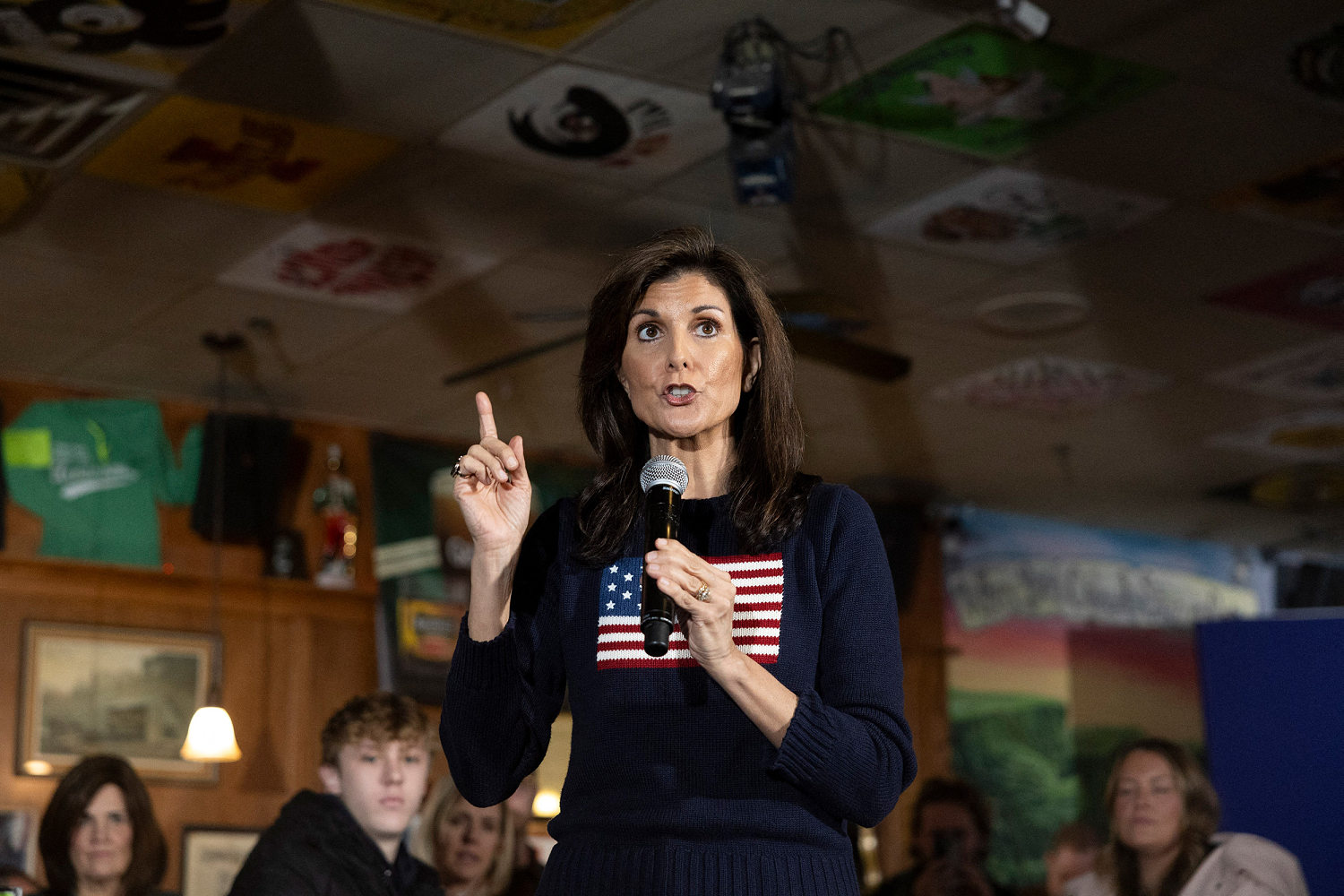

Here, the parallel between ’24 and ’00 is clear, with former United Nations ambassador Nikki Haley now taking over McCain’s role.

Granted, he’s pushed harder in Iowa than McCain ever did, while spending less time than DeSantis and investing more than the Florida governor did in New Hampshire. Haley himself nodded to the New Hampshire-centric strategy when he told a Granite State crowd last week, “You know how to do it.” You know Iowa is starting. You know you fix it.” (Haley later insisted to Iowan that she was joking.)

Like McCain, Haley has already won favor in New Hampshire. Exactly how much is up for debate new polls show Trump leading by various measures. But whatever the exact difference, Haley seems poised to make Trump sweat in New Hampshire in a way he never did in Iowa.

And like McCain, he’s doing so by specifically appealing to the state’s independent voters, who are not only allowed to vote in Republican primaries but regularly flock to those races in droves. Every recent poll in New Hampshire showed Haley ahead of Trump among independent voters, with roughly half of his overall support coming from that group. It goes well with self-described moderators as well as those with college and graduate degrees.

McCain’s resemblance to Haley’s budding New Hampshire coalition is uncanny. In McCain’s case, it became a political earthquake. He didn’t beat Bush on the first night of 2000; crushed him, 49% to 31%. The scale of the explosion surprised even Bush loyalists, who were pessimistic about the state. Exit polls told a dramatic story: Among independent voters, McCain beat Bush by 41 points, 60% to 19%. The spread among middle-level people was 36 points.

Immediately, the race for the GOP nomination was changed. Harnessing the fledgling internet, McCain absorbed millions of small-dollar donations almost overnight. McCain vs. The Bush contest stunned the media, which painted it as a David vs. Goliath battle and took on an editorial tone that was transparently sympathetic to McCain. It seemed the coronation had been cut short, and now there was going to be a real battle – one that McCain might just win. This was the emerging storyline.

Initial fidelity test phase

McCain likened the New Hampshire victory to catching lightning in a bottle, which is exactly what Haley is looking for in the state now. In his case, he probably doesn’t need a margin of about 20 points to accomplish this; Any victory over Trump would be a major upset.

If he succeeds, the focus will turn to South Carolina, as it did in 2000 — where things turned sour for McCain in 2000, and if it does, it could be for Haley. much, although South Carolina is his homeland.

Much has been said and written about the 2000 South Carolina Republican primary. Suffice it to say, it was ugly, for the most infamous reason Allegations of underground efforts by Bush allies To smear McCain.

But fundamentally, the seeds of McCain’s success in New Hampshire hurt him in the Palmetto State, where the GOP core electorate is more conservative.

Bush and his team capitalized on McCain’s appeal to independents, his frenzied media coverage, and even the sudden enthusiasm of some prominent Democrats for him. Bush viewed the South Carolina election as a test of loyalty. The primary voters were the liberal media’s candidate, non-Republicans, and even some, even as Bush put it, a big hit among Democrats? Or were they loyal to the Republicans?

McCain said his appeal outside the GOP could make him more electable. The polls back it up: A CNN/USA Today poll showed Bush ahead of the presumptive Democratic nominee, Vice President Al Gore, by 9 points and McCain by 22 points. At a rally in 2000, McCain declared: “I say to the Independents, Democrats, Libertarians, vegetarians: Come and vote for me!”

On the night of the primary, Bush won the debate easily. And yet the exit poll told a brilliant story. Although South Carolina has no official party registration, independent voters have favored McCain, as have New Hampshire. But they made up a much smaller part of the electorate.

Meanwhile, those who said they were Republicans favored Bush by 41 points. Overall, about 80 percent of Bush voters identified as Republicans; For McCain, it was less than 40 percent. And with such a different mix of Republicans and independents in the electorate than in New Hampshire, Bush won South Carolina by 13 points and McCain’s momentum stalled.

The 2000 campaign would continue for a few more weeks, and McCain would score another dramatic victory in Michigan. But by then the dividing line was clear. Michigan’s open primary rules allowed independents and Democrats to vote, and they made up more than half of the GOP electorate — giving McCain enough votes to carry the state. But it reinforced Bush’s key message about his opponent’s reliance on the other team’s voters. After a disappointing Super Tuesday, McCain withdrew from the race and the nomination went to Bush.

If he can take off in New Hampshire, the McCain story offers an obvious cautionary note for Haley. A victory backed by non-Republicans (and no small number of anti-Trump voters) will be viewed with skepticism by Republicans elsewhere. That would be especially true if Haley McCain were to enjoy anything like the media coverage she received 24 years ago.

The Republican Party has changed dramatically since 2000, but a strong element of loyalty remains among its core voters; now, though, it’s less an allegiance to the party itself and more to Trump. Trump could put voters in South Carolina and beyond to the same basic test that Bush did: are you with me or with them? And as in 2000, there aren’t many primaries and caucuses where the “them” side will be big enough to win.