With nearly 60 million ballots already cast, anyone interested in the presidential election is trying to figure out where the race stands.

Even with so many votes cast, it’s hard to know what that means. Many people have yet to vote, and it is not known exactly how many people will vote or how they will be divided. But there’s one measure of early voting data that may be more telling about the final results: the number of new voters who have already voted.

And an NBC News Decision Desk analysis of state voter data shows that as of Oct. 30, there are signs of an influx of new female Democratic voters in Pennsylvania and new male Republican voters in Arizona.

The early votes of new voters — voters who did not appear in 2020 — are of particular interest because they are the votes that could change what happens in 2024 compared to the last presidential election. (Who voted in 2020 and didn’t show up this time is also important, but it’s impossible to know before Election Day.)

In many of the seven states that are already close battleground states, the number of new voters exceeds the 2020 margin between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. For example, in Pennsylvania, Biden beat Trump in 2020 by 80,555 votes. More than 100,000 new voters have already cast ballots in Pennsylvania this year, with more to come.

We don’t know how these new voters voted, but looking at who they are can give us clues as to how 2024 will be different from 2020. Party registration doesn’t perfectly predict a voter’s choice, but new voters who choose to register as Democrats are more likely to vote. are more likely to vote for Vice President Kamala Harris, and new voters who register as Republicans are more likely to vote for Trump. As a result, in swing states (Arizona, Nevada, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania) where voters can officially register for a party, new voters may have some clues about the 2024 election.

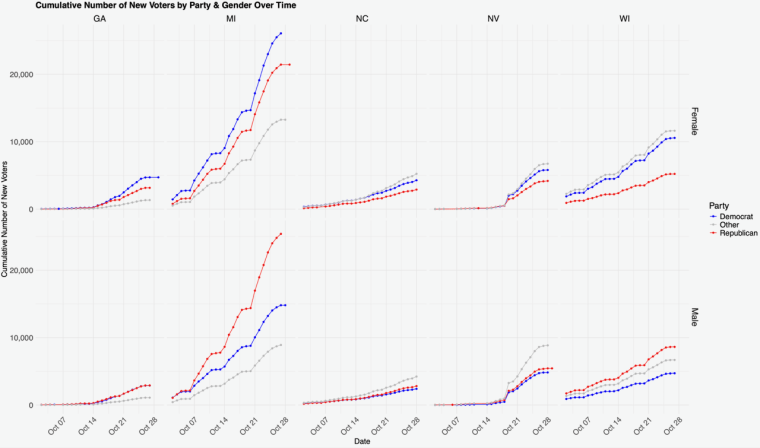

(In Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin, where voters are not officially registered with a party, the best we can do to predict the partisanship of new voters is based on local voting patterns and demographics — data that is quite noisy and can sometimes be wrong.)

In these states, the gender of new voters is also public information, shedding light on the relationship between gender and party registration among new voters against an electoral backdrop that hinges on a number of gender-related political issues, such as abortion. (Some states offer a “non-binary” or “other” option on their voter registration forms, which few voters use so far.)

New voters from Pennsylvania are dominated by female Democrats

Let’s start with Pennsylvania—and not just because it’s thought to be the nearest state according to pollsand also because the number of new voters who voted there already exceeded the 2020 margin. If everyone voted for the same candidate again starting in 2020, these new voters would decide the race.

Data from Pennsylvania show large differences in the number of new voters cast by both party registration and gender. More new voters are registered Democrats than Republicans, and new female voters widen the partisan gap. New male voters are slightly more likely to be Democrats than Republicans, but among new female voters, Democrats outnumber Republicans about 2 to 1.

The number of new voters who decide not to officially register with either party complicates the picture, as the number of new unaffiliated voters is nearly the same as the difference between the number of new Democrats and new Republicans. That means unaffiliated voting could either erase or expand the advantage that registered Democrats currently have among new early voters.

Reverse trend in Arizona: Male Republicans lead the way

Turning to Arizona, the opposite pattern emerges. Although there were fewer new voters than in Pennsylvania — in part because early voting started later in Arizona — the 2020 margin in Arizona was also smaller: just 10,457 votes.

Already, the number of new voters (86,231 as of Tuesday) is more than eight times the 2020 Biden-Trump margin in Arizona. In Arizona, the largest share of new voters by far are male Republicans.

Unlike in Pennsylvania, new female voters are slightly more likely to be registered Republicans than Democrats in the state. But so far, the Republican advantage in new Arizona voters is largely driven by male voters.

Again, there are a significant number of new voters who choose not to affiliate with either party, and how they vote could easily change the Republican registration advantage seen among new voters who vote early.

In other swing states, it’s a mixed picture

Looking at the remaining five swing states, different patterns emerge – and no clear takeaway.

There is a large clear difference in the behavior of new male and female voters in Michigan, although the results in Michigan are complicated by the fact that there is no registration by party there and the difficulty of predicting the partisanship of Michigan voters without this information. he has seen big mistakes in the past. But according to these estimates, projected Democratic women slightly outnumber projected Republican women among new voters, while projected Republican men nearly double the number of projected new Democratic men.

Wisconsin, like Michigan, suggests a strong correlation between gender and partisanship among new voters—new female voters skew slightly for Democrats and new male voters slightly skewed for Republicans. However, the number of new voters predicted to be unaffiliated warrants caution in trying to read too much into these estimates.

In the other states with actual party registration data — North Carolina and Nevada — there is a new pattern: voters unaffiliated with either party are by far the largest group of new voters among both men and women. How these independents vote is obviously critical and also unknown – again underscoring the difficulty of drawing strong conclusions using early voting data.

One thing is clear, however: These voters could be decisive, as the number of votes cast by the new 2,024 electors already exceeds the margin of vote in many of the closest states in 2020. They enter a polarized electorate and an election many have been waiting for. near Except in a few states where available data begins to suggest a larger story, the number of unaffiliated new voters — or the lack of party registration in key states — makes it difficult to know exactly how early voting will turn out. the results of this year’s elections.

In such circumstances, looking at aggregate early voting reports in hopes of predicting the future seems like a pointless exercise. Our pro tip: Take a walk and enjoy the fall weather instead.